Brendan Hughes's true republicanism

Notes from the writings of an avatar of a direction not taken

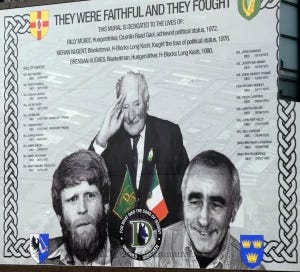

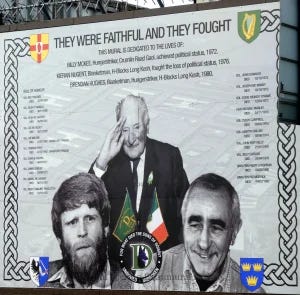

The first – or last depending on your direction of travel – of the murals on Belfast’s famous International Wall as Divis Street becomes the Falls Road features the faces of three Provisional IRA volunteers to whom the mural is dedicated: the first Officer Commanding (OC) of the Provisionals’ Belfast Brigade, Billy McKee (central in the mural); the first blanketman in Long Kesh, Kieran Nugent (left); and another Belfast Brigade OC, Brendan Hughes (right).

These are three men whose lives are linked chronologically: McKee’s hunger strike in 1972 led to the introduction of Special Category Status for paramilitary prisoners during the ‘Troubles’; in 1976 Nugent initiated the blanket and dirty protests in the H-block section of Long Kesh against the revocation of that status; and Hughes led and partook in the 1980 hunger strike that followed the failure of years of protests to reclaim the status. The Dark: Selected Writings of Brendan Hughes, a long overdue collection of Hughes’s writings published by Iskra Books last year, outlines other connections in their lives.

In his post-Good Friday Agreement (GFA) days, Hughes positioned himself as a republican critic of the deal, disillusioned with the fact the killing and dying had been bookmarked by a peace deal that accepted the Six Counties’ place in the British state and gave all power to convene a border poll to the British Secretary of State. In his arguments against the emerging ‘republican’ status quo, Hughes often used McKee and Nugent as touchstones: McKee for their shared experiences of working for “exploitative cowboy builders”1 from their own community generations apart; and Nugent for his being discarded by the republican movement, left to die an early death in 2000 in his early forties having been branded a “river rat”2 after his descent into alcoholism found him often drinking on the banks of the River Lagan.

Hughes’s citation of McKee and Nugent’s example is indicative of his gradual falling away from the mainstream of Irish republican orthodoxy, or rather that orthodoxy’s gradual falling away from him. For Hughes, the principles that had taken him to war against the British state and its presence in Ireland, those of “James Connolly, of Liam Mellows, of true republicanism”3 remained the principles that saw him die in poverty in Belfast’s Divis Tower block of flats — an epicentre of republican activity during the war. The columnist Robin Livingstone, better known as Squinter, wrote in an introduction to an exhibition by the photographer Judah Passow that Divis was “a grim place when our flat was new in 1970” and a “grimmer place when we moved out a year later”. Hughes died there in 2008, with 37 additional years of neglect and the effects of the British army commandeering the tower as an observing post having taken hold. By that point, Divis Tower was the only Divis Flats tower block that hadn’t been demolished.

What caused Hughes’s divorce from the centre of the Provisional movement and his erstwhile best friend and Long Kesh cellmate Gerry Adams was the abandonment of “people who went to war trying to bring about a democratic socialist republic”4 (such as himself and Nugent - McKee was a staunch Catholic and anti-socialist) by what Hughes came to term the “Armani suit brigade”5, those such as Adams who had abandoned the Armalite entirely in favour of the ballot box. It is telling of the difference between Adams and Hughes that the writings in The Dark are all dated after Hughes’s involvement in the ‘Troubles’.

Adams, under his own name in pamphlets and the pen name Brownie in An Phoblacht, was a prolific writer of political analysis throughout the seventies; it is known that tension existed within the Ballymurphy faction of the Provisionals, where Jim Bryson had raised concern with Adams’s lack of involvement with military actions. Hughes, having lived a life of constant military action, moving from safehouse to safehouse between stints of imprisonment, did not take to writing publicly until he found his private opinion ignored in the GFA era.

The views that we find in The Dark are that of a man who, like his hero Che Guevara, became a revolutionary thinker through his active participation in a revolutionary situation rather than through academic sources. As former IRA prisoner Anthony McIntyre writes in his introduction “there was no need on his part to read Paulo Freire”;6 Hughes instinctively became what Freire termed a responsible subject, those whose developing consciousness “leads the way to the expression of social discontents precisely because these discontents are real components of an oppressive situation”.7

A childhood amidst the poverty of mid-century west Belfast, witnessing the plight of the Bantustans of South Africa during his time in the Merchant Navy, starving almost to death for his vision of Irish freedom, and reading of the Palestinian cause while imprisoned created the Brendan Hughes that is known today — a democratic, internationalist republican socialist who never wavered because he could not bring himself to abandon “the anonymous poor, the real heroes and heroines of this struggle”.8

“For many, when all is said and done more will be said than done,” McIntyre writes. “Brendan reversed the order of things on that front,”9 or, as his contemporary revolutionary Ghassan Kanafani would have had it, Hughes understood that it is through armed struggle that colonial situations are “ultimately decided”.10 While he acknowledged that the time for war was over by the time the GFA was signed, Hughes nevertheless stood his ground politically at a time when the republican closing of ranks became increasingly dangerous, as with the Provisionals’ killing of the Real IRA’s Joe O’Connor11 in 2000. That his main ask – that republicanism become open to debate once again, as it had been in the huts of Long Kesh – is so often repeated in this collection is proof of his consistency and proof of it falling on deaf ears.

Directly around the corner from the mural of Hughes, McKee, and Nugent, on Northumberland Street, is another D Company mural, this one of Charlie Hughes and the Palestinian revolutionary Leila Khaled. This pairing would no doubt have pleased Brendan, who spent much of his time in the early 2000s aiding Palestinian solidarity causes; The Dark features a recollection of him almost oversleeping his duty of driving a Palestinian Solidarity Campaign bus to Dublin in 200212 and fond reminisces of his cousin Charlie13, who was killed by Joe McCann of the Official IRA during internecine feuding.

While Hughes and McCann would be linked in real life forever by this action, there is between them a certain symbolic symmetry. Both are seen as avatars of the road not taken in their respective sides of the Provisional/Official split. What might have happened had republicanism altered itself along Hughes’s line — which by 1998 was one of understanding that the time of violence was over but unwillingness to enter the partitionist halls of power — seems now as distant an idea as McCann’s wish for the Officials to maintain their militancy amidst their conversion to reformism.

Writing about Charlie’s death over 30 years on, Hughes affords no sympathy for the Officials, stating that his cousin was “murdered by reformists”, but in an entry mere pages later pays tribute to Patricia McKay, a 19-year-old Officials volunteer who died in a joint Provisional-Official gun battle with the British army in which Hughes partook in 1972.14 Hughes also writes of his relief at having not pulled the trigger while standing over a young British soldier “crying for his ‘mummy’”.15 The Hughes on display in The Dark is a thinker possessing deep humanism situated in an inhumane situation created by Britain and the spokes of history, propelled into the fights against Britain and reformism that defined his life by “a love of people, a love of justice, a love of truth – and a hatred of power that gives privilege to the few and abuse to the many”.16

Hughes wrote that “an Irish republican is a dissident first and foremost”.17 It was the willingness to enter a political structure where “the façade has been cleaned up but the bone structure remains the same”18 that he could not abide. If, as Hughes argued, “all the questions raised in the course of this struggle have not been answered”19, it is not difficult to guess what Hughes would make of the so-called historical nature of Michelle O’Neill’s ascension as “First Minister for all” at Stormont, or of Sinn Féin meeting with Joe Biden and other luminaries of the US political apparatus while Gazans were being slaughtered in their thousands by American weapons.

The murals beside Hughes, McKee, and Nugent have recently been painted over, making way for a long mural depicting the destruction of Gaza and the dispossession of its people, with the words of the murdered poet Reefat Alareer’s “If I Must Die” scrolled across it atop a red ribbon. Hughes died working for Palestinian solidarity and demanding space be made for debate over international causes within Irish republicanism.

Outside of Ed Moloney’s Voices from the Grave: Two Men’s War in Ireland and now The Dark, Hughes remains oddly marginalised within the recent history of Ireland despite his significance in the course of the most recent phase of prolonged violence against the British presence in Ireland. This lack of engagement with Hughes is perhaps an indicator of who controls such narratives and what they do not permit to enter into accepted discourse. That The Dark contains two never-before-seen communiqués smuggled out of Long Kesh to his brother Terry, one from the 1980 hunger strike and the other from the 1981 strike, ensures that the study of such a figure can be furthered.

While the current status of the Palestinians and the present shape of Sinn Féin would undoubtedly depress him further were he alive today, it would perhaps have brought a chuckle to his lips and raised some hope within him to see the booing of Sinn Féin representatives at a recent Palestinian solidarity event in Belfast over their visit to the White House. While party figures were quick to call those disruptors Trotskyites and wreckers, the fact remains that the Palestinian question largely hews to the republican-loyalist dichotomy in the Six Counties. Those doing the booing were most likely members of Sinn Féin’s base, where dissent on this issue had been successfully stifled. “With the war politics had some substance. Now it has none,” Hughes remarked grimly in 2000.20 The return of all-out war in Palestine has brought with it global blowback, and as Hughes said, “our past has shown that all is never lost”.21 It is not always the case that every fissure heralds a larger change, but in some cases, voices can be raised, murals can be painted over, fences can be torn down, and things can begin anew.

Brendan Hughes. 2023. The Dark: Selected Writings of Brendan Hughes. Edited by Róisín Dubh. Madison: Iskra, p. 25.

Ibid, p. 134.

Ibid, p. 49.

Ibid, p. 46-47.

Ibid, p. 73

Anthony McIntyre in The Dark, p. 4.

Introduction of Donaldo Macedo in: Paulo Freire. 2005. Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 30th Anniversary Edition. New York: Continuum, p. 36.

The Dark, p. 109.

McIntyre in The Dark, p. 3.

The Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War, directed by Masao Adachi and Kôji Wakamatsu (Wakamatsu Productions, 1971).

Suzanne Breen. 14 October 2000. “Leading ‘Real IRA’ member is shot dead in Ballymurphy”. The Irish Times. Accessible at: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/leading-real-ira-member-is-shot-dead-in-ballymurphy-1.1109180

The Dark, p. 105

Ibid, p. 117-122.

Ibid, p. 124-125.

Ibid, p. 115.

Ibid, p. 91.

Ibid, p. 55.

Ibid, p. 27.

Ibid, p. 27.

Ibid, p. 27.

Ibid, p. 26.

My name is colm Boston.

Charlie Hughes was my Nans brother.

God rest them all